Contradictory, confusing, inaccurate

Link/reference: Gaps and flaws in the traditional boundaries of our work

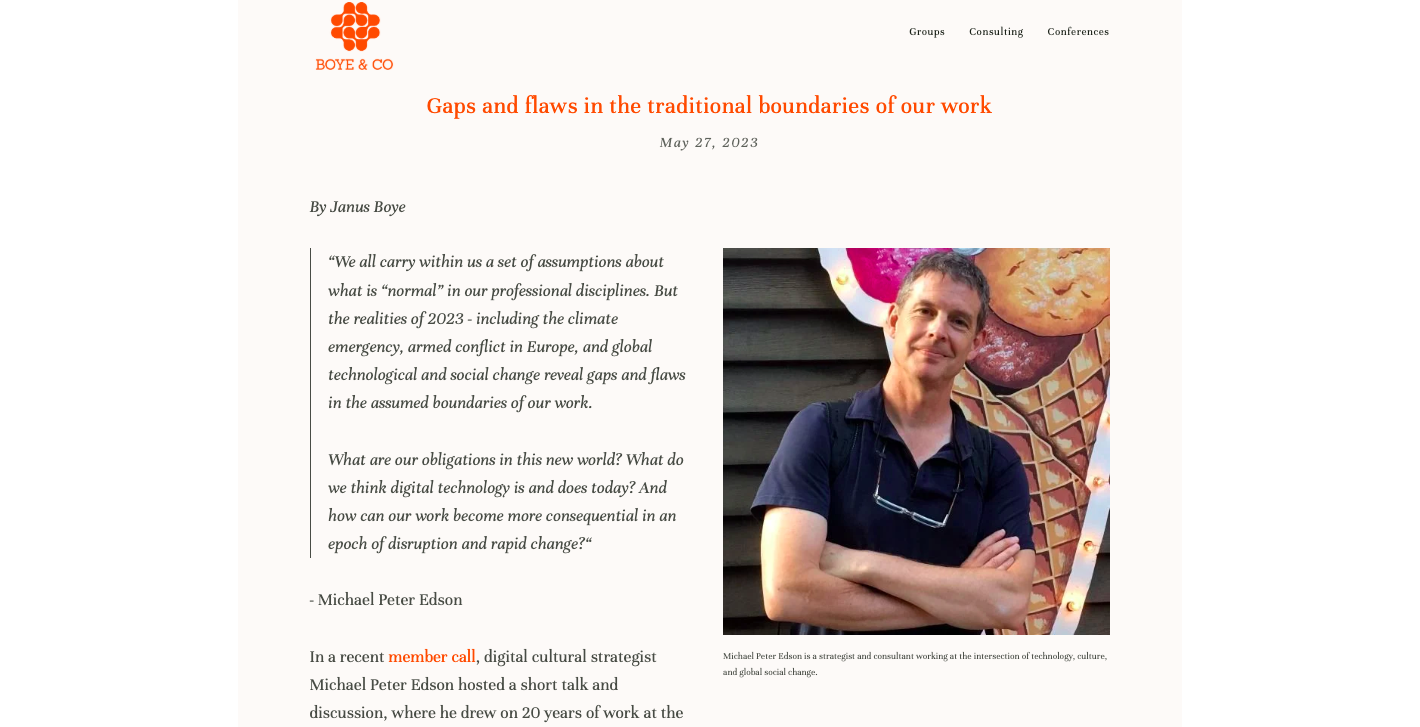

This is a good writeup of my ideas about creating new norms of practice in the cultural sector. (…I had kind of forgotten that I had put these ideas together so clearly!)

Gaps and Flaws in the Traditional Boundaries of Our Work, (PDF) summary of my presentation/discussion by Janus Boye.

What it means to be a professional in an epoch of accelerating change.

The Big Frikin’ Wall that stands between us / our organizations and the work we should be doing in society.

The “inner dialogue” we all have with the norms/expectations of our professional disciplines.

The “handoff” between different sectors of society.

The taboos around activism (“we have been miseducated…”).

Link to U.N. Museum TEDx talk

For the convenience of some new collaborators, I dumped the video and transcript of my 2016 TEDx talk about the Museum for the United Nations onto a convenience page here:

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the theme of top-down & bottom-up change, cultural institutions as catalysts for the know-how and creativity of others (rather than the instution as an exclusive/proprietary authority), and citizen participation is still relevant (and a largely unfulfilled vision) today.

“The Internet really is ass now”

Near-valueless concepts

An Advanced Civilization

Not preordained

Careless People, Facebook and de Tocqueville

For reference, this is the opening paragraph of Bleak House:

LONDON. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snow-flakes gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas in a general infection of ill-temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if the day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.

Elon stopped believing in Mars

Only a void

Like the Russians in 1917, we live in an era of rapid, sometimes unacknowledged, change: economic, political, demographic, educational, social, and, above all, informational. We, too, exist in a permanent cacophony, where conflicting messages, right and left, true and false, fash across our screens all the time. Traditional religions are in long-term decline. Trusted institutions seem to be failing.

Techno-optimism has given way to techno-pessimism, a fear that technology now controls us in ways we can't understand. And in the hands of the New Obscurantists — who actively promote fear of illness, fear of nuclear war, fear of death, dread and anxiety are powerful weapons.

The supporters of the New Obscurantism have also broken with the ideals of Americas Founders, all of whom considered themselves to be men of the Enlightenment. Benjamin Franklin was not only a political thinker but a scientist and a brave advocate of smallpox inocula-tion. George Washington was fastidious about rejecting monarchy, restricting the power of the executive, and establishing the rule of law. Later American leaders - Lincoln, Roosevelt, King-quoted the Constitution and its authors to bolster their own arguments.

By contrast, this rising international elite is creating something very different: a society in which superstition defeats reason and logic, transparency vanishes, and the nefarious actions of political leaders are obscured behind a cloud of nonsense and distraction. There are no checks and balances in a world where only charisma matters, no rule of law in a world where emotion defeats reason—only a void that anyone with a shocking and compelling story can fill.

Connected Audience Conference — slides, references, and notes

Image of program description listing speakers

Thursday I’ll present a talk at Connected Audience 2025: Factors, Challenges and Opportunities of Cultural Participation for Youth sponsored by the IfKT, Institute for Cultural Participation Research (Institut für Kulturelle Teilhabeforschung), Berlin.

The session will be moderated by Ryan Auster of the Museum of Science, Boston, with Kaly Halkawt Lundström of Stockholm University and Dimitra Christidou and Sofie Amiri from the National Museum, Oslo, Norway.

My contribution will be about why we need to create new kinds of museum institutions — everywhere, urgently, starting yesterday — that support young people as legitimate “doers” and problem-solvers in society, and how we approached developing the voice, know-how, and agency of of our visitors at the Museum of Solutions in Mumbai.

I’ll post the full talk (both shortened and full versions) as well as slides, notes, and a transcript below.

Slides and Video

Slides (Google Slides, pdf)

Photos of MuSo (my Google Photos album. All photos CC-BY Michael Peter Edson)

Transcript (in progress)

References

“The right to the future tense”

This is one of the recurring themes of Shoshana Zuboff’s stunning 2018 book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. Honestly, Google’s AI did a better job summarizing this concept than any single source I’ve found, including Zuboff’s book iteslf: Shoshana Zuboff defines the "right to the future tense" as the fundamental human ability to imagine, intend, promise, and construct a future. It is the essence of free will, autonomy, and the ability to make meaningful choices about one's life. Zuboff argues that surveillance capitalism, which involves companies using data to control and predict behavior, encroaches upon this right by limiting individual agency and autonomy. (Google Gemini on May 18, 2025, citing an interview with Zuboff in The Harvard Gazette and a book review on Taylor & Francis Online.)

“Information-deficit model of behavior change.” Wikipedia.

“The knowing-doing gap”

Dupont, L., Jacob, S. & Philippe, H. Scientist engagement and the knowledge–action gap. Nat Ecol Evol 9, 23–33 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-024-02535-0

Interesting article from an insurance-industry website: Bridging the climate knowledge – action gap, by Hélène Galy. September 16, 2022. For all the improved climate science, our existing tools are holding us back from urgent action. Science is not enough: we need longer-term planning and reappraisal of values.

Moving from climate knowledge to climate action, Canadian International Development Research Centre (IDRC), September 20, 2023

Jose Antonio Gordillo Martorell, Founder and CEO of Cultural Inquiry

Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation

On the Opening of the Museum of Solutions (my blog; linkedIn)

Webinar, Create Dangerously: Museums in the Age of Action

via NEMO — the Network of European Museum Organizations, 14 February 2023 (Video, slides and background)

Looking in the wrong place

“Lego ad 1981” via Imgur user Ms Spicy Brain.